|

Loading

|

|

|

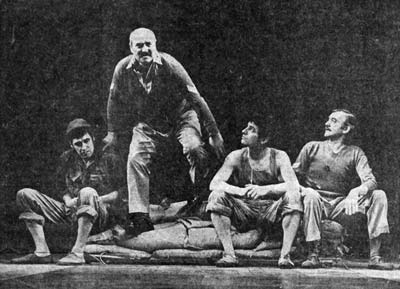

Crete and Sergeant Pepper

by John Antrobus

Royal Court Theatre, 24 May 1972

The English Stage Company

The English Stage Company was formed in 1956 with the idea of presenting new plays performed by a permanent company of actors. Within months its financial position was precarious to say the least, but the extraordinary vitality of "Look Back in Anger" by John Osborne, both artistic and commercial, crystallised the theatre’s policy as being a theatre for new plays. The value of a permanent company was reviewed critically, The energy of the theatre was directed towards the finding of new writers and presenting their work in the best possible way.

The loss of a permanent company led to the Royal Court’s careful casting policy giving a new currency to the actors who were employed. The care in finding the right actor for the part, often involving young or unknown actors being cast in leading parts gave the actor at the Court a special value, without the dangers inherent in permanent companies of a part being found for an actor, rather than a play being put on for the public.

When William Gaskill took ever the artistic direction of the Royal Court from George Devine in July 1965 he started with a company presenting new work, but it seemed not even a considerable increase in public subsidy could sustain a permanent company doing new work in repertoire. Companies have been assembled at the Royal Court for special seasons, for example the Wesker trilogy in the D.H. Lawrence season and the Edward Bond season. George Devine was a well-known teacher, and William Gaskill has also

As early as " " and " " in (date), work based primarily on the actors has had a place in the Royal Court's life. In (date) a studio open to all members of the acting profession was formed. Last year a studio was run for the actors in current Royal Court productions, both in Sloane Square and the West End, as well as the many young actors in whose development the theatre felt involved, and the current production in the Theatre Upstairs is based on the work and ideas of its performers.

The Royal Court Theatre is a writers’ theatre run by directors, which has always been sensitive to and affected by the actors who have worked there. There are few young actors of reputation today who have not spent a a formative part of their working life at the Court. The Royal Court’s consistency its work with actors is informal and flexible but not insensitive or pragmatic. It has devoted itself to the development of young talent while always including established masters of their craft. It is this drawing together of talents in different stages of their formation which has been one of the main and sustaining processes of this theatre. In fact the workers at the Royal Court Theatre are more likely to agree on the merits of an actor than anything else!

What is regarded as good acting at the Royal Court Theatre is more an informing value than a style. It can be described perhaps as a feeling for observed reality, a kind of humanism, a belief that the actor is uniquely himself, with a task to portray another human being described by a particular writer, and to meet the demands of this with accuracy and complexity. People come to the Court to see new plays, but the actual contact with another human being remains the theatre’s touchstone.

The company formed for "Crete and Sergeant Pepper" is largely made up of actors who have played here before, but as usual the play has its own demands and presents us with the opportunity of welcoming some new actors to our theatre.

note Peter Gill, 1972

| Pepper | Bill Maynard |

| Jones | Bernard Gallagher |

| Milligan | James Hazeldine |

| Jackson | Stephen Rea |

| Spotty | Tony Douse |

| Billings | John McKelvey |

| Commandant | Lenard Fenton |

| Dentist | Nicholas Smith |

| Naval Officer | Peter Childs |

| MP Officer | Jeremy Child |

| Guard | Chris Malcolm, Don Hawkins, Robert Hamilton, Brian Hall |

| Director | Peter Gill |

| Designer | Douglas Heap |

| Costumes | Deirdre Clancy |

| Lighting | Andy Phillips |

| Assistant Director | Jonathan Chadwick |

| Costume Supervisor | Jenny Tate |

| Production Manager | Andrew Treagus |

| Deputy Stage Manager | Juliet Alliston |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Robert Hendry |

| SSM | Titus Grant |