|

Loading

|

|

|

Noble takes flight

By John Gross, Sunday Telegraph, 6 February 2000

THERE

are 10 principal characters in The Seagull. They come on stage

trailing personal histories which in many cases we can only guess at. They have

complicated relationships with one another. And, Chekhov being Chekhov, our view

of them keeps shifting, as we see them through different eyes, or in a different

light.

THERE

are 10 principal characters in The Seagull. They come on stage

trailing personal histories which in many cases we can only guess at. They have

complicated relationships with one another. And, Chekhov being Chekhov, our view

of them keeps shifting, as we see them through different eyes, or in a different

light.

This isn't to say, as people. sometimes do, that Chekhov abstains from moral judgment. A mean act is seen clearly as a mean act in his work, a generous act as a generous one. But he also knows that motives are mixed, that circumstances vary, and that most characters defy a simple either/or verdict. He might well have taken as his motto a wise injunction from Henry James: "Never say you know the last word about any human heart."

Openness and a multiple viewpoint are the main reasons why a Chekhov play, however often it is produced, can still come up as fresh and surprising. Always assuming, of course, that it is staged with intelligence and sensitivity. And both those qualities are in plentiful supply in Adrian Noble's admirable new production of The Seagull at the Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon.

Though the production couldn't be as good as it is without the constant give-and-take of ensemble playing, pride of place must go to Penelope Wilton's magnificent portrayal of the actress Arkadina. Is she funny? Yes. When she tells Nina, "I am sure you must have talent," there is an edge to her voice worthy of Noel Coward. (What a Judith Bliss in Hay Fever she would make.) Is she moving? Yes. I have never seen the reconciliation after the row with her son Konstantin in the head-bandaging scene better done. (What a Gertrude in Hamlet she would make.) But mostly it is Arkadina's ruthless professionalism that she conveys, with unfailing skill.

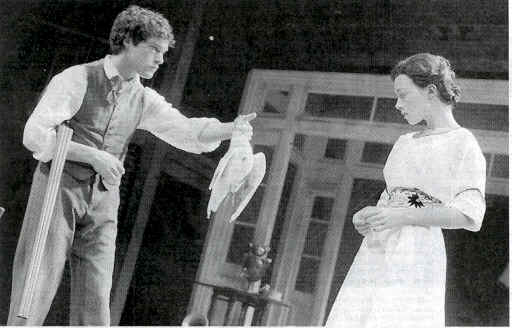

There is another exceptional performance from Justine Waddell as Nina. When she peers at Arkadina's lover, the writer Trigorin, with adoration, you feel, yes, that is Nina. And she brings out the tough streak which performers who stress the ingénue often miss. In the last act, touching though she is, it occurred to me that Nina's life might not really be over, that she might be a bit of a potential Arkadina herself.

Richard Johnson as the self-confident doctor is as good as you would expect; Richard Pasco, as Arkadina's ailing, disappointed brother, is even better. John Light's Konstantin slightly fades at the end — the tearing up of the manuscript isn't as heartrending as it should be — but in other respects he gives a fine, edgy performance. And though Nigel Terry's Trigorin doesn't quite convince as an author, he and Wilton are both splendid in the scene where Arkadina re-establishes her sexual hold over him. What a contrast between their subtle playing and the ludicrous rolling around during the same scene in the National Theatre's last Seagull.