|

Loading

|

|

|

Where Seagulls dare

Chekhov's classic is full of grumblers, but audiences at Stratford will find little to complain about

The Seagull, The Swan, Stratford-on Avon, Kate Kellaway, The Observer, Sunday February 6, 2000

'I

am in mourning for my life. I am unhappy,' says Masha in an unselfpitying tone.

Her unhappiness is a perky accessory, set at a tilt, like her black hat.

'I

am in mourning for my life. I am unhappy,' says Masha in an unselfpitying tone.

Her unhappiness is a perky accessory, set at a tilt, like her black hat.

Niamh Linehan plays Masha with cartoon vehemence, as though she were not in charge of her body, as if it were worked by vodka and sexual energy. She droops, staggers, swoons. She is a lively mourner. She sums up something of the spirit of Adrian Noble's marvellous RSC production of The Seagull . It shows exactly what Chekhov knew: how intimate the comic and tragic are.

In Chekhov's plays it is possible to be convivial and lonely at the same time. And critical. The Seagull is full of critics. There is not a character who does not have something to complain of: boredom, middle age, the countryside, lack of fame. Life must be shaken like an unsatisfactory eiderdown. There are, to adapt Tolstoy, so many ways of being unhappy.

The miraculous thing about this production is its 'lived in' quality. There is a sense of the life of the characters pre-dating the play and having a future beyond it. The set (designer: Vicki Mortimer) seems effortless: a lawn with a fringe of spring flowers, a straggle of crocuses; there is nothing fancy (save an unscheduled special effect on the press night. A curtain caught fire and play was temporarily suspended. If the cast was thrown, they did not betray it).

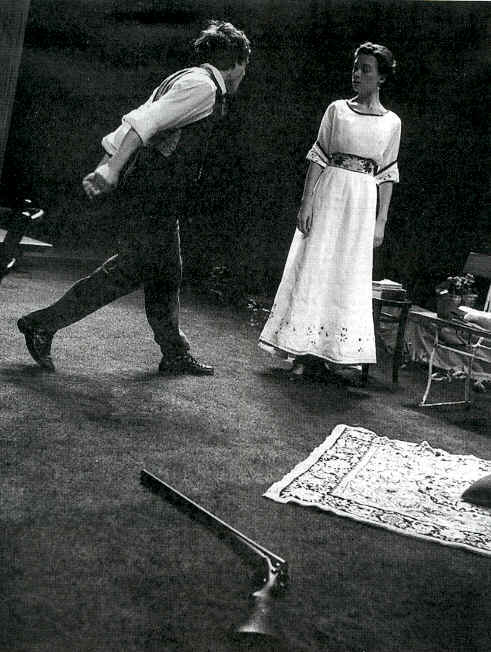

Konstantin (John Light) is as bad at living as at writing. Light shows how hard it is to be young. It is a convincing performance, of forced smiles, self-dramatising misery. As Nina, Justine Waddell is arresting too. She arrives on stage as if shot from a bow: fast, direct, involuntary. Waddell shows how ardour may tip into despair. She acts the injured Nina superbly, announcing she is a seagull with deluded intensity.

Penelope Wilton is perfection as the middle-aged actress, Arkadina. Gloriously overdressed in her showy silver and royal blue ensemble, Arkadina is relentlessly auditioning for life. Wilton has a wonderfully mobile face but also a trick of robbing her features of expression at moments when her words say too much. She gets her combination of heart and heartlessness absolutely right. Arkadina treats men like foolish puppies. She is at once magnificent and pathetic when she begs Trigorin not to leave her. Contempt glitters beneath her words. And when she says: 'He is mine again', she lets us see that though her need was real, her passion was all performance.

Trigorin (Nigel Terry), the mediocre novelist, looks more like a suave fisherman than a man of letters. Terry skilfully suggests a man disagreeably benign, a horrid mixture of complacency and disappointment. Standing about, looking old and irresolute in his gumboots, or brandishing his dirty crushed handkerchief, you can see he is ripe for Nina's flattery.

There are excellent performances elsewhere, especially from Richard Johnson as Dorn and Richard Pasco as Sorin. And while it might seem redundant of the RSC to have commissioned a new version of The Seagull when Tom Stoppard has recently written such a good one, Peter Gill's uncontrived version is a match for Stoppard's.