|

Loading

|

|

|

Virtuoso work all round

Alastair Macaulay reviews Speed-the-Plow, New Ambassadors' Theatre, London WC2, Financial Times, 20 March 2000

What matters most in a play is rhythm and there are more rhythms than one. The metre of the individual lines; the length of speeches; the pacing of dialogue; the rate at which the meanings of the play unfold; the gradual disclosure of the play's inner structure. With some playwrights, you don't think about rhythm because they make it transparent. You can't miss it in the plays of David Mamet, however. He and Harold Pinter are the two greatest masters of surface rhythm in English language theatre today. It is easy to feel all this in London's production of Mamet's Speed-the-Plow, beautifully directed by Peter Gill.

You feel the larger rhythm of the play's structure, too. The Hollywood movie executive Gould plays a tough guy's game with his colleague Fox until suddenly the temp, Karen, seduces him into an apparently uncharacteristic change of policy. The initial scene between the two men part-jocular, part-combative, highly satirical, brilliantly entertaining feels unrelaxed, air-conditioned, so that Karen, played here by the American stage-and-movie actress Kimberly Williams arrives like a breath of fresh air. The room temperature changes, the pace eases.

Then, however, this little breath of fresh air becomes a major wind of change. Williams shows that Karen is the most ambiguous -inscrutable character in the play. How naive is she and how calculating? How destructive and how liberating? How pretentious and how sincere? The way your reaction to her keeps shifting is the most troubling element in the play, and perhaps the most stimulating.

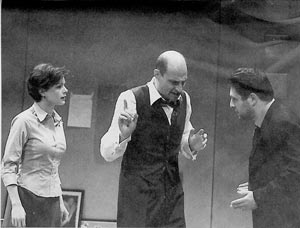

As Gould, Mark Strong is seldom off the stage, and even seasoned admirers of his acting will find his performance as Gould surprisingly rich. He's an enthralling mixture of strength and weakness, a spiffing macho veneer that gradually reveals first, fissures, then pulp beneath. How wonderfully he listens: he seems not to move a muscle, but, now and then, the slightest widening of the eyes seems like a seismic shift. And his body-language throughout -trying always to open itself out expansively, trying always to relax masterfully, yet always showing a certain defensiveness and control -tells its own story. Then there's the particular fun of watching the playwright-director Patrick Marber meeting these two skilled actors on equal terms as Fox. His is the most musicianly rhythm of all even in such details as the way he repeats the word "yesterday", and the most audaciously choreographic style. How perpetually tense he stays; how seldom he ever comes out of profile the profile in which he keeps his attention locked on Gould. So his Fox emerges as intent, oblique, pugilistic; and the fierce eagerness of eye and mouth register too.

Virtuoso work all round, in a cruel comedy whose satire on various kinds of American bullshit seldom relaxes, and which never flags for a moment. Many of its exchanges are among the funniest in London theatre today. Yet I don't find, on leaving the theatre, that the play goes on growing in my head. While the individual lines coruscate dazzlingly, it sometimes feels, if you attend to the deeper feelings they lodge in your mind, that you are actually being hammered rather slowly and unyieldingly hammered by Mamet. Speed-the-Plow never invites you in, and it has no largeness of spirit. Bravura theatre; wonderfully unlike anything else in the West End at present; but more guarded than any of its characters.