|

Loading

|

|

|

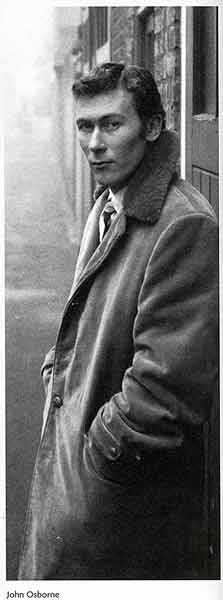

John

Osborne

John

Osborne

Cavalier and Roundhead

by John Heilpern

John Osborne was a Christian and therefore a sinner. A lacerating sense of sin ran through the latter part of his life. His Protestantism which he returned to in crisis as he approached fifty wasn't a pose or a righteous countryman style mocked by some as "Christian Blimp": He read the Lesson in church, usually attending at Evensong. But he went to church only when he felt cheerful! When he felt low, he didn't go.

"God's got enough problems without hearing mine," he explained, and he meant it.

Faith became central to Osborne and to how in his later angst he viewed the wormy mess of life. Yet, when he had just turned 30 and there was no evidence of churchgoing or God in his life, he made the remarkable choice of the ecstatic rebel Luther for his historical drama in 1961. The gutter candour and poetry of Luther Kenneth Tynan wrote admiringly might have come from the pulpit oratory of Donne.

Here's Martin Luther in a pivotal speech of the play:

"And I sat in my heap of pain until the words emerged and opened out, 'The just shall live by faith. My pain vanished, my bowels flushed and I could get up. I could see the life I'd lost. No man is just because he does just works... This I know; reason is the devil's whore, born of one stinking goat called Aristotle, which believes that good works make a good man. But the truth is that the just shall live by faith alone. I need no more than my sweet redeemer and mediator, Jesus Christ."

To paraphrase Osborne on that stinking goat Aristotle, good works don't necessarily make a good man. The turbulent artist lives and dies on his own shaky plateau somewhere between God's embrace and the envy of the patron saints of mediocrity. Yet society prefers to see the artist as a fine upstanding example of humanity blessed with the virtuous normality of a bank manager.

The need still exists to believe that good art is created by good people. How could Osborne be so cruel? goes the question often asked about him with indignant, reflexive piety. He notoriously reached for his poisoned pen to damn Jill Bennett in print when he learned of her suicide. But we may also ask how the saintly Tolstoy could abandon his poor, bullied wife on a railway station? How could James Joyce neglect his insane daughter? T.S. Eliot's neglect of his insane first wife? Or Proust's sexual thrill at watching hatpins stuck into rats? How, for that matter, could a genius composer whose talent was kissed by God behave like a farting idiot savant? Are we all Salieris now? Do we still believe, in spite of all evidence to the contrary Mozart's infantilism, Coleridge's morphine, Pound's Fascism, Baudelaire's syphilis, O'Neill's alcoholism, Math's suicide, Wagner's anti-semitism, Hemingway's bullet, Van Gogh's ear that good and great art can only be created by good and great and normal human beings?

Thank God I'm normal

I'm just like the rest of you chaps, Decent and full of good sense

I'm not one of these extremist saps. For I'm sure you'll agree

That a fellow like me

Is the salt of our dear old country...(Archie Rice's song, The Entertainer)

Who or what is "normal"?

But with Osborne, reverse logic applies. How could someone who wrote with such devastating candour and savagery seem so agreeable? The disparity between Osborne's mythic public reputation as a snarling Rotweiller and the private, generous man who many people knew was striking. His diffident mildness dumbfounded strangers when they met him, as if they anticipated an ogre.

He was an apparent paradox: a sweet ogre, a Cavalier and a Roundhead, a traditionalist in revolt, a radical nonconformist who hated change, a protector of certain musty old English values who wasn't nice and normal. He was a patriot for himself, a patriot for England. But when it came to his battles and his beliefs, I was to learn that he could be like the uncompromising Luther nailing his principles to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg.

© John Heilpern 2001, adapted from his authorised biography of John Osborne, to be published by Chatto and Windus

John Osborne (1929-1994)

| 1956 | Look Back in Anger (staged at the NT in 1999) |

| 1957 | The Entertainer |

| 1958 | Epitaph for George Dillon co author Anthony Creighton |

| 1959 | The World of Paul Slickey |

| 1959 | A Subject of Scandal and Concern (television play) |

| 1961 | Luther |

| 1962 | Plays for England Under Plain Cover and The Blood of the Bambergs |

| 1964 | Inadmissible Evidence (revived at the NT, 1993) |

| 1965 | A Patriot for Me |

| 1966 | A Bond Honoured (an adaptation of Lope de Vega's La fianza satisfecha, NT at the Old Vic) |

| 1968 | Time Present and A Hotel in Amsterdam |

| 1971 | West of Suez |

| 1972 | A Sense of Detachment and an adaptation of Ibsen's Hedda Gabler |

| 1974 | The End of Me Old Cigar and two television plays, Jill and Jack and The Gift of Friendship |

| 1975 | Adaptation of Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray |

| 1976 | Watch it Come Down (premiered at the Old Vic and transferred to the Lyttelton for its inaugural season) |

| 1981 | A Better Class of Person, An Autobiography 1929-1956 published |

| 1988 | New version of Strindberg's The Father (at the NT's Cottesloe Theatre) |

| 1991 | Almost a Gentleman, An Autobiography 1955-1966 published |

| 1992 | Déjà vu |

| 1994 | Damn You England, Collected Prose published |

| 1999 | Two volumes of autobiography published together by Faber as Looking Back: Never Explain, Never Apologise. |