|

Loading

|

|

|

A History of the Irish Future

| Now for our Irish wars, We must supplant those rough-headed kerns Which live like no venom else But only they have privilege to live. |

| Shakespeare, "Richard II", Act II, Scene I |

Originally Ireland lived at the limit of endurance because it was once the limit of the western world. Here, tribes stood and fought their pursuers or were "civilised " under their feet. Ireland, then, was an imperial shock-absorber which has never recovered from the shock.

| For the great Gaels of Ireland Are the men that God made mad, For all their wars are merry, And all their songs are sad. |

| G K Chesterton |

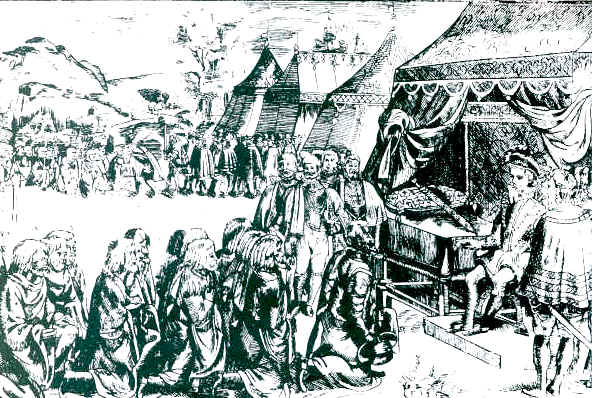

No side has ever completely won or lost, a factor in the recurring tragedy. The 5th century Gaels, Central European in origin, with their lawyers, druids, poets and Olympiads, showed the decline in the Roman Empire by raiding and enslaving its citizens in England and Wales. The Romans, astute inventors of the concept of empire, had never invaded Ireland. Now their disrupted twilight confirmed an earlier evident opinion that occupying Ireland would not be worth the trouble. But one enslaved Roman, St Patrick, later converted Ireland eternally to the Church of Rome, making ancient history of Gaelic divorces.

| History is the nightmare from which I am trying to awake. |

| James Joyce |

In the Dark Ages it was Irish Catholicism which colonised Europe with its exquisite manuscripts and its monasteries across France, Germany and Italy. The monks were widely cut down by helmeted Norsemen in the 9th century who, according to the established pattern, intermarried yet remained a separate ethnic strain. They rimmed Ireland with ports, stockaded a city, Dublin, and were naturally half- suppressed themselves by the powerful Gaelic King Brian Boru at the Battle of Clontarfin 1014.

It was "at the creeke of Baginbunne / Ireland was lost and wonne" for England, originally, by the advance forces of the Norman warrior Strongbow in 1170. By the mid-13th century, Ireland was feudally administered from its Norman keeps. Tyrone and Donegal remained powerfully aloof, however, northern territories for the first time becoming English anxieties.

Some Normans became "more Irish than the Irish", and this was made a punishable offence. The Statutes of Kilkenny, 1366, were a re-conquest of Normans by Normans: they outlawed intermarriage with the Irish, "degenerate" Irish garb, and made mandatory the English tongue.

And yet there followed a great uprising of Gaelic culture where, for one Tudor century, Ireland was ruled by the powerful Earls of Kildare, Gaelo-Norman Viceroys in principle, uncrowned kings in specific. Even Poynings' Law of 1494, whereby the English King could veto any impudent legislation by the Irish parliament, could not curb them. Finally an impulsive rebellion in 1534 enabled Henry VIII to execute six of the Kildares, and for the next four hundred years the Irish state was administered by Englishmen.

When

Elizabeth I's aggressive extension of territory finally put to flight the

northern Earl of Tyrone, Ulster became a lush political desert ready for

plantation. English and Scottish settlers were encouraged to fortify new towns -

and to safeguard their hew electoral advantages — which widely dispossessed the

native Irish and made Ulster a successful Protestant anomaly in a country which

had resisted the Reformation.

When

Elizabeth I's aggressive extension of territory finally put to flight the

northern Earl of Tyrone, Ulster became a lush political desert ready for

plantation. English and Scottish settlers were encouraged to fortify new towns -

and to safeguard their hew electoral advantages — which widely dispossessed the

native Irish and made Ulster a successful Protestant anomaly in a country which

had resisted the Reformation.

Caught between the divine righteousness of both Charles I and Cromwell, Ireland saw England's difficulty as its opportunity. The rebellion of 1641 was an attempt to regain planted territory; this involved some persecution of Protestants, soon to be eclipsed by Cromwell's campaign in Ireland.

Cromwell's aim was to vaporise the Royalist cause in Ireland and revenge the wronged Dissenters. With a notorious sincerity he did so, slaughtering the populations of Wexford and Drogheda. Irish poor were sold as slaves to the West Indies, Catholic priests outlawed, all "transplantable persons" ordered west to barren Connaught by the Settlement Act of 1652.

The improvement of Irish Catholic fortunes under the sympathetic James II simply encouraged his English parliament to offer William of Orange a Protestant throne. As his last hope James rallied Catholic Ireland in 1690 for the Battle of the Boyne, but was defeated by William on the 12th of July, a date celebrated by Orangemen today as glorious and immortal.

Now that the Protestant Ascendancy had firm control of Ireland, the Penal Laws were passed in 1695 to prevent the original Gaelo-Normans from improving their social position. No Catholic could enter parliament, the army or the law. No Catholic could buy land or inherit land. Catholic bishops and monks were banned, mass was conducted in secret. The next century passed in seeming peace.

With

American and French Republicanism in the air, Catholics and Dissenters alike

were awakened by Thomas Paine's book The Rights of Man, and in 1791

Ulster Protestant radicals formed a secular independence movement, the United

Irishmen. Wolfe Tone led them: a Protestant who advocated Catholic emancipation,

he is still commemorated as the first true Republican.

With

American and French Republicanism in the air, Catholics and Dissenters alike

were awakened by Thomas Paine's book The Rights of Man, and in 1791

Ulster Protestant radicals formed a secular independence movement, the United

Irishmen. Wolfe Tone led them: a Protestant who advocated Catholic emancipation,

he is still commemorated as the first true Republican.

The United Irishmen's rebellion of 1798 was humane and abortive. The English General Lake had been sent beforehand to disarm Ulster in a memorable fashion, so that only a core of dedicated revolutionaries rose up to be defeated. Arriving too late with a French fleet, Wolfe Tone committed suicide rather than be hanged as a criminal.

If America was lost to Britain, Ireland could be saved.

| What people! They haven't a penny to lose, more than half of them have not a shirt to their back, they are real proletarians and sans culottes, and Irish besides — wild, ungovernable, fanatical Gaels. Nobody knows what the Irish are like unless he has seen them. If I had two hundred thousand Irish I could overthrow the whole British monarchy. |

| Engels, 1842, writing of O'Connell's movement |

William Pitt was convinced that to avoid further rebellion Ireland must be constitutionally unified with Britain as soon as possible. Since 1782, when Henry Grattan's agitation had forced Britain to modify 15th-century legislative restrictions, Ireland's separate parliament had enjoyed new opportunities for independence. Enjoyed them thoroughly and corruptly, for the majority of members represented "pocket" or "rotten" boroughs. After some bribery and intimidation by Lord Castlereagh, the Irish parliament voted enthusiastically for its own dissolution and the 1801 Act of Union gave Ireland representation at Westminster instead. Catholics, however, still could not stand for parliament.

Daniel

O'Connell, "The Liberator", was to change this, giving Catholics their first

sense of unity and power. O'Connell's flamboyant oratory at monster meetings

proved that mass Catholic movements could make peaceable changes: the Catholic

Relief Bill of 1829 made most public offices open to Catholics, but this victory

was limited by a change in the voting qualification to exclude O'Connell's poor

supporters. When in 1843 he began calling for a new, independent Irish

parliament, the government banned his mass meeting at Clontarf. As a

constitutional man O'Connell gave way to the ban, but never recovered his

political authority.

Daniel

O'Connell, "The Liberator", was to change this, giving Catholics their first

sense of unity and power. O'Connell's flamboyant oratory at monster meetings

proved that mass Catholic movements could make peaceable changes: the Catholic

Relief Bill of 1829 made most public offices open to Catholics, but this victory

was limited by a change in the voting qualification to exclude O'Connell's poor

supporters. When in 1843 he began calling for a new, independent Irish

parliament, the government banned his mass meeting at Clontarf. As a

constitutional man O'Connell gave way to the ban, but never recovered his

political authority.

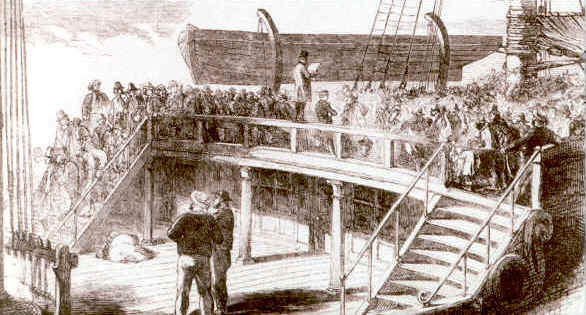

As social control, however, bans were no competition for the blight on a potato. The Great Famine of 1845-49 showed this clearly. At first, when the disease hit crop after crop, Britain took some relief measures, buying American grain and employing the starving through public works. But the new laissez-faire Liberal government of 1846 bought no more food and the next winter was the worst in Irish memory. Mass evictions were carried out by many landlords — the starving died of exposure. Yet throughout the famine, landlords profitably exported immense quantities of grain. The hungry who tried to seize the corn were weak and easily suppressed.

The

population dropped by two million: half starved, half emigrated to America,

sometimes in "coffin ships" which sank from overcrowding. Among the surviving

refugees were leaders of the failed Young Irelanders' rising of 1848 who, with

assurances of Irish-American backing, planned a modem, professional secret

society to help establish an Irish Republic.

The

population dropped by two million: half starved, half emigrated to America,

sometimes in "coffin ships" which sank from overcrowding. Among the surviving

refugees were leaders of the failed Young Irelanders' rising of 1848 who, with

assurances of Irish-American backing, planned a modem, professional secret

society to help establish an Irish Republic.

| England has destroyed the conditions of Irish society. First of all she has confiscated the lands of the Irish, then by "Parliamentary decrees" she has suppressed Irish industry; finally, by armed force she has broken the activity and the energy of the Irish people. |

| Karl Marx, 1853 |

Between this subversive movement and Ulster, the chasm widened. With its prosperous mills and shipyards Ulster had allied itself with the Industrial Revolution, not the subsequent revolution of the bitter, post-famine Fenians.

The secret Fenian Brotherhood, founded in 1858, had intense support among the Irish population in America and believed in revolution by force, "sooner or never". The American part of the organisation was invaluable for its ability to function openly, tapping the new, relative prosperity of famine-embittered emigrants — but Fenianism offered more status in the New World than practical help for the Old Country and Irish Fenian leaders became critical of the infighting American "tinsel patriots". The American Civil War was useful to Irish brigades as training for the Fenian insurrection of 1867. This as usual was a passionate token rising which stood for widespread Republican sentiment but was easily suppressed.

| Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life ... His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the "poor whites" to the "niggers" in the former slave states of the USA. The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money.He sees in the English worker at once the accomplice and the stupid tool of the English rule in Ireland. |

| Karl Marx, 1870 |

Now, after seven hundred years, England felt the first domestic effects of a supposedly domestic war: in Manchester the successful attempt to rescue two imprisoned Fenians caused the death of a constable. Three men among the Fenian rescue crowd were hanged for the murder without having actually committed the deed.

To many British, these Fenians were the Manchester Murderers who had brutally raised "the Irish Question" — to many Nationalists, they were the Manchester Martyrs who had attempted a valid Irish answer. Their respective leaders were bent on a more co-operative antagonism. Gladstone won the general election in 1868 by declaring, "My mission is to pacify Ireland", while Ireland's new, uncrowned constitutional king, Charles Stewart Parnell, proclaimed, "I have a parliament for Ireland within the hollow of my hand". He was not the last to boast this.