|

Loading

|

|

|

"Il faut de l'audace, encore de l'audace, toujours de l'audace" (Danton)

A main source of Büchner's for Danton's Death was Auguste Mignet's History of the French Revolution (1824), and this is much quoted in the following notes by Shirley Matthews

"Paris is as full as an egg:' wrote Camille Desmoulins, bursting with excitement, "Versailles the same." It was 5 June 1789, nearly five years before the period covered by Danton's Death.

"The present Revolution", Robespierre declared soberly, "has shown us in a few days the greatest events that the history of man can offer." It was 23 July 1789. Not for the last time, it seemed to many that the Revolution had come and gone.

In the four preceding weeks the anticipation which had drawn the crowds had been amply fulfilled. On 17 June the Commons declared itself unilaterally a National Assembly - defying an attempt to shut it up, and out - by an oath in the King's indoor tennis court not to disperse until they had established a Constitution. On 14 July the Parisians stormed the Bastille. Three days later Louis XVI accepted a patriotic cockade in the Hotel de Ville in Paris. And on 23 July the Assembly refused his command to resume business, unless it was as representatives of the nation as a whole. People throughout France had asserted themselves.

In August the new Assembly began its work: feudalism was abolished, and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was declared.

In October the women of Paris, trailing the National Guard in their wake, marched on Versailles demanding bread, and induced the royal family to return with them to the capital to playa central role in government. "You have learnt no doubt of the great Revolution which has been accomplished:' Camille Desmoulins wrote on 8 October: "Consummatum est. The King, the Queen, the Dauphin are in Paris." The Assembly undertook, between then and April 1791, a major programme of reform, the reorganisation of France, within the framework of a constitutional monarchy.

The King, however, was not reconciled to this curtailment of his privileges and tried to escape abroad with his family; They did not get far. On 20 June 1791 the royal party were arrested on the road at Varennes and brought back to Paris under guard.

Now the "republican party" began to appear. "The struggle which was first between the Assembly and the Court, then between the constitutional deputies and the aristocrats, then between the constitutionals themselves, now began between the constitutionals and the republicans" (Mignet). On 17 July 1791 republican demonstrators were shot down by the National Guard on the Champs de Mars.

The King finally approved the new Constitution on 13 September, and the Assembly was dissolved for the elections. But the new Assembly was not content to consolidate the work of the old, and "the Revolution, which should now have finished, recommenced" (Mignet).

In

February 1792 France's two most powerful neighbours, the monarchies of Austria

and Prussia, with the secret connivance of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette,

formed an alliance with the intention of crushing the Revolution and restoring

the King to absolute power. France declared war on 20 April.

In

February 1792 France's two most powerful neighbours, the monarchies of Austria

and Prussia, with the secret connivance of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette,

formed an alliance with the intention of crushing the Revolution and restoring

the King to absolute power. France declared war on 20 April.

On 10 August 1792, the people of Paris took matters back into their own hands and stormed the Tuileries, imprisoning the royal family. The monarchy was abolished, a republic declared, and Danton became Minister of Justice. "More than any other he had been involved on 10 August. He was a giant of a revolutionary. He condemned no means, so long as it served his end. ..Ardent, morally lax, he abandoned himself in turn to his passions and his party. He was formidable in politics when it was a question of achieving his aims, nonchalant once they were his. This powerful demagogue was a mixture of vice and the opposite ... A revolution in his eyes was a game, where the winner, if he had need of it, took the life of the loser. For him the well-being of his country was above law, above humanity, which explains his outrages after 10 August and his return to moderation when he believed the republic secure" (Mignet).

|

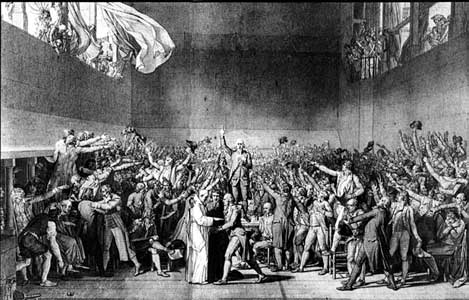

| David's famous drawing, The Tennis Court Oath, is dated 1791, two

years after the event. Robespierre clasps his hands on his heart as he takes

the oath, administered by the President of the Assembly. Despite his egalitarian policies, which included legislation to regulate prices and incomes, Robespierre did not long survive Danton, his great adversary. In June 1794 he persuaded the Assembly to pass a law depriving prisoners of the right to a defending counsel and making death the sole punishment. Fear of him grew, and a great procession in his honour alienated many. On 26 July he rashly spoke in the Assembly of the removal of a group of unspecified enemies. The next day he, Saint-Just, and Couthon were arrested, condemned without trial, and guillotined on 28 July. |

Beside Danton stood Robespierre, "whose talents were average and whose character was vain ... who owed it to his inferiority that he came forward among the last, which is always a great advantage in a revolution" (Mignet). It was his ambition, supported by the extreme Jacobin party which he headed, to oust the moderate Girondins from their position of power in the Assembly, and to supplant Danton.

The King was guillotined on 21 January 1793. On 31 May the Girondins were arrested. Unrest followed, countered with measures of increasing severity by the Jacobin government. Hundreds went to their deaths in the "Terror." The Girondins were executed on 31 October 1793 and this cast a long shadow, severing personal and political ties. Danton, sickened, retreated from politics, but returned in December in time to avert an attack on him, at the Jacobins Club, as a "moderate". Robespierre seemed to support him, then persuaded him to join the government in defeating the extreme left Hébertists.

The next day, Camille Desmoulins launched his paper, Le Vieux Cordeliel, under the banner Live Free Or Die. He deviated from the line agreed with Robespierre, supported Philippeau's appeal for mercy to the government's opponents, and proposed a "Committee of Clemency:"

Jacques Hebert and his followers were guillotined on 24 March 1794, exposing Danton's followers as the last group who could offer opposition to the government.

Danton, detached, relaxed, was still visibly the great hero of the Revolution. He had told Frenchmen "Il faut de l'audace, encore de l'audace, toujours de l'audace" (You must dare, dare, and dare again). But on 5 April 1794, he and his friends "perished, the latest and last defenders of humanity and moderation; the last men to wish for peace between the victors of the Revolution and to show pity for those they had conquered. All perished, and still the men in power had as many victims to strike down as they had enemies. A man stopped in this bloody adventure only when he was killed himself." (Mignet).