|

Loading

|

|

|

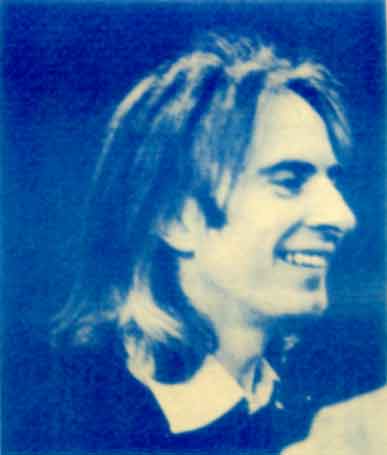

Peter

Gill by Christopher Hampton

Peter

Gill by Christopher Hampton

(from the programme of the July 1976 Royal Court Theatre first performance of Small Change by Peter Gill)

When I worked for a brief and, in retrospect, ludicrous spell in the Literary Department (Dramaturgie) of a huge German theatre, the Hamburg Schauspielhaus, one of my tasks, alongside of writing reports in execrable German on the complete plays of Swinburne, was to draw to the attention of my colleagues supposing I should happen to encounter one of them, wandering disconsolately through featureless corridors in the bowels of the budding, plays newly produced in London which I thought might be of interest to them. The name of D.H.Lawrence excited a great deal of advance interest, but I knew when I distributed copies of the text of The Daughter-in-Law, its impenetrable dialect printed in miniscule greenish typescript in a Royal Court programme (price 1/-) that its acceptance could hardly be immediate. After all, the play had been sitting around England for 50 odd years, waiting for someone to comprehend its potential, realise its atmosphere and add Lawrence to the alarmingly short list of really interesting early twentieth century British dramatists.

The production of the Lawrence Trilogy, with its meticulous attention to detail, unforgettable images and emotional truthfulness was one of the landmarks of my theatre going life, and its influence on a whole line of work in the theatre and on television was far reaching. What's more, all this was widely recognised at the time. What has not been nearly as fully acknowledged, it seems to me, is the quality and range of Peter Gill's subsequent work in the theatre. For example and at random: Ruffian on the Stair, the first production I had seen of an Orton play, which successfully accommodated the peculiar glittering solemnity of his style; Peter Gill's own plays, The Sleepers' Den and Over Gardens Out, which apart from being beautifully observed and acted with musical precision, made the most resourceful use I have ever seen of the Theatre Upstairs' space; Life Price by Jeremy Seabrook and Michael O'Neill which found a style of slightly heightened, bleak, but not cheerless naturalism, and incidently proved the official view that people would not come to the theatre if the seats were free and would not enjoy it if they did to be nonsense; Twelfth Night with the Royal Shakespeare Company, which was quite simply the best Shakespeare production I had seen in years, tender and melancholy without being in the least sentimental, and harsh and clean, without being in the least austere, the sexual ambiguities defined in a way that was neither evasive nor crude; and most recently, Edward Bond's The Fool, a production of exemplary severity, economy and clarity, which (like the play) was mysteriously under-rated.

A dislike of ostentation and a refusal to over simplify are not of course virtues which commend themselves to English critics: but there are other qualities in Peter Gill's work which are not so easily ignored. These include a powerful sense of imagery, which, even when one quarrels with the interpretation of a play (as I did in the case of The Duchess of Malfi at the Royal Court) is memorably imposing; a shrewd appreciation of the possibilities of individual stages (the only occasion I worked with Peter was a translator of Hedda Gabler, which he directed at the Shakespeare Festival Theatre, Ontario, on a stage which is comically inappropriate for the play, but which he managed to use more fully and imaginatively than many a Shakespeare production had, despite its intransigent shape); and a talent for finding and developing young actors and actresses and coaxing remarkable performances out of them. Above all, both as writer and director, he has an unerring eye for illuminating detail: and no one has a surer grasp of the strangeness of reality.