|

Loading

|

|

|

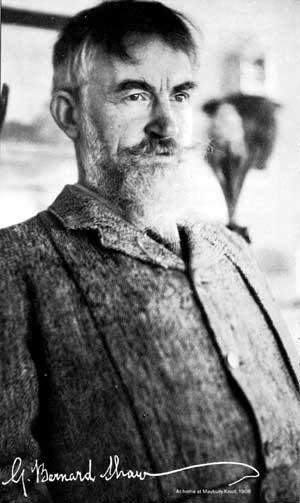

George Bernard Shaw and the World of Major Barbara

by Peter Lewis

(from the programme of Peter Gill's 1982 National Theatre production of Major Barbara)

Major Barbara was the third new Shaw play to be presented at the Court Theatre in 1905, Shaw's annus mirabilis. He had made his reputation for comedy in March, when the King attended a command performance of John Bull's Other Island and laughed so much that he broke his chair. Man and Superman, shorn of the Don Juan in Hell act, played to packed houses in October and, in November, came Major Barbara. With these three plays, Shaw converted the theatre into a forum of ideas and debate, where audiences came to be provoked, to be forced to think and to carry on the argument after the curtain fell. He was in his 50th year and he had indisputably arrived before the general public as England's leading playwright.

Poverty and the Salvation Army

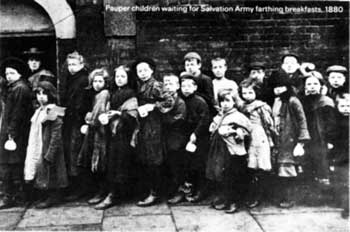

Shaw's

theme in Major Barbara was poverty and what could or should be done

about it. It was a timely subject. Although Britain was still at the summit of her

imperial power in 1905, there were nearly a million people receiving Poor Law relief.

One person in 36 was a pauper, over two-thirds of them women and children. In London

the proportion was higher, one person in 31. On 1 January 1905, there were in London

148,000 paupers, including 1,365 "casual paupers", most of them described as vagrants,

who spent the night on the streets or in the workhouse casual wards, or Spikes.

(There are still 23 Spikes, now called Government Reception Centres, in England

and Wales, catering for 30,000 homeless.)

Shaw's

theme in Major Barbara was poverty and what could or should be done

about it. It was a timely subject. Although Britain was still at the summit of her

imperial power in 1905, there were nearly a million people receiving Poor Law relief.

One person in 36 was a pauper, over two-thirds of them women and children. In London

the proportion was higher, one person in 31. On 1 January 1905, there were in London

148,000 paupers, including 1,365 "casual paupers", most of them described as vagrants,

who spent the night on the streets or in the workhouse casual wards, or Spikes.

(There are still 23 Spikes, now called Government Reception Centres, in England

and Wales, catering for 30,000 homeless.)

Their number had increased substantially since 1878, when William Booth founded the Salvation Army and became its first General. In 1888 the Army had opened its first hostel for down-and-outs (it still runs many today). Booth's book, In Darkest England, claimed that one person in ten lived "below the standard of the London cab-horse", which was at least assured of food, shelter and warmth. From the beginning women enjoyed equal status with men in the Salvation Army as officers, soldiers and preachers, thanks to his wife, Catherine Booth's initiative. There were many Major Barbaras.

Shaw had shared pitches with the Salvation Army when he went speaking in the East End streets. When a newspaper described a noise as "worse than a Salvation Army band", he wrote to complain, vouching for the bands' excellence on his authority as a well-known music critic. As a result, General Booth invited him to a mass meeting at the Albert Hall and he was seated among the Army leaders.

"I led the singing in my crowded box with tremendous gusto. A tribute to my performance came from a young Salvation lass who, her eyes streaming with tears, grasped both my hands and cried 'Ah! We know, don't we?"' The next day he wrote to the manager at the Court Theatre, J.E. Vedrenne, "When the roll is called up yonder — I'LL BE THERE. I stood in the middle of the grand tier centre box and sang it as it has never been sung before. The Times will announce my conversion tomorrow. What other author would do that for his management?"

When

the play opened he persuaded a box-full of Army commissioners to attend in full

uniform, although they had never attended a theatre before. The Army had refused

his invitation actually to take part in the second act, but had lent the uniforms

for the production. They came to his aid when the play was treated by some critics

as a jibe at the Army on the ground that the Salvationists were too light-hearted

and took money from the whisky distiller. "The Army received this with the scorn

it deserved, declaring that Barbara's fun was perfectly correct and characteristic.

The only incident that seemed incredible to them was her refusal to accept the money.

Any good Salvationist, they said, would, like the Commissioner in the play, take

money from the devil himself and make so good use of it that he would perhaps be

converted, for there is hope for everybody."

When

the play opened he persuaded a box-full of Army commissioners to attend in full

uniform, although they had never attended a theatre before. The Army had refused

his invitation actually to take part in the second act, but had lent the uniforms

for the production. They came to his aid when the play was treated by some critics

as a jibe at the Army on the ground that the Salvationists were too light-hearted

and took money from the whisky distiller. "The Army received this with the scorn

it deserved, declaring that Barbara's fun was perfectly correct and characteristic.

The only incident that seemed incredible to them was her refusal to accept the money.

Any good Salvationist, they said, would, like the Commissioner in the play, take

money from the devil himself and make so good use of it that he would perhaps be

converted, for there is hope for everybody."

Shaw's Originals

|

|

| Oswalde Yorke as Bill Walker, Miss E Wynne-Mathison as Mrs Baines | |

|

|

| Dawson Milward as Charles Lomax | Louis Calvert as Undershaft, Granville-Barker as Adolphus Cusins |

|

|

| Annie Russell as Barbara, Oswalde Yorke, Clare Greet as Rummy Mitchens, Doroty Minto as Jenny | |

The inspiration for Barbara was not, however, a Salvation Army lass but an actress, Eleanor Robson. Shaw had half fallen in love with her when she played on the London stage the previous year (her career was in New York). He wrote to her: "I have begun another play and lo! there you are in the middle of it ... I swear I never thought of you until you came up a trap in the middle of the stage and got into my heroine's empty clothes and said Thank you: I am the mother of that play ... the heroine is so like you that I see nobody in the wide world who can play her except you." It was not to be. Terms could not be agreed with her American manager and she recommended Annie Russell, who finally played the part.

The identification of Barbara's lover, the professor of Greek, Adolphus Cusins, was quite specific: Professor Gilbert Murray, whose verse translations of Euripides had just appeared. Murray wrote the verses which Cusins declaims and was frequently consulted by Shaw, who wrote in a prefatory note on its publication, "The play stands indebted to him in more ways than one."

One of these ways was the loan of his spectacles, which Harley Granville-Barker wore when playing the part. "Barker has been cultivating the closest resemblance to you in private life for a fortnight past," wrote Shaw to Murray, "Everybody recognised it the moment the spectacles went on." All three men were friends. Murray had married the daughter of the Countess of Carlisle, a Whig peeress, temperance reformer and leader of the women's Liberal Federation. She ran salons for Liberal intellectuals at her house, Castle Howard. She was described, for all her Liberal sympathies, as an "empress" and was the model for Lady Britomart.

It is far more difficult to discern an original for Andrew Undershaft, the armaments manufacturer whose remarkable philosophy that poverty is the only crime provides the dramatic mainspring of the play. There is no shortage of candidates, for this was the era of the private arms trade buccaneers whose salesmen ranged the world and who certainly subscribed to Undershaft's description of the Faith of an Armourer: "to give arms to all men who offer an honest price for them, without respect of persons or principles."

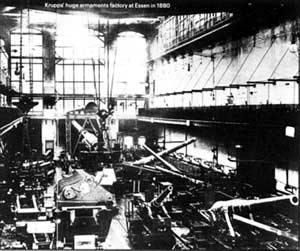

Arms and Armourers

In

1905 (the year the first Dreadnought was built) the biggest arms makers in Britain

were Armstrong, Vickers and the Nobel Dynamite Trust. Sir William (later Lord) Armstrong

had built up his firm until it was second only to Alfried Krupp, selling armaments

from China to Peru. To Armstrong's mansion on Tyneside came (in person) the Shah

of Persia, the King of Siam, the Emir of Afghanistan and many a military delegation

to buy arms. "Those who use the means we supply must be responsible for their legitimate

application," said Armstrong, who professed to believe that the new engines of war

would make war less barbarous.

In

1905 (the year the first Dreadnought was built) the biggest arms makers in Britain

were Armstrong, Vickers and the Nobel Dynamite Trust. Sir William (later Lord) Armstrong

had built up his firm until it was second only to Alfried Krupp, selling armaments

from China to Peru. To Armstrong's mansion on Tyneside came (in person) the Shah

of Persia, the King of Siam, the Emir of Afghanistan and many a military delegation

to buy arms. "Those who use the means we supply must be responsible for their legitimate

application," said Armstrong, who professed to believe that the new engines of war

would make war less barbarous.

Vickers' chief salesman was the legendary Sir Basil Zaharoff, who claimed proudly: "I sold armaments to anyone who would buy them. I was a Russian in Russia, a Greek in Greece, a Frenchman in Paris. I made wars so that I could sell arms to both sides."

Alfred Nobel, who had patented dynamite in 1867, bringing himself an immense fortune, was a strange, withdrawn, misanthropic man who wrote poetry in imitation of Shelley. He was interested in pacifism but claimed "My factories may end war sooner than your peace congresses. The day two army corps can destroy each other in one second, all civilised nations will recoil from war and disband their armies." This was not Shaw's belief. Says Undershaft: "The more destructive war becomes, the more fascinating we find it." Who was the greater realist?

Nobel had doubts, for in 1901 he instituted the Peace Prize that bears his name. Shaw was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 1925. He only accepted it after making arrangements so that he need not take the money. Having been besieged by begging letters on this account, he remarked: "I can forgive Alfred Nobel for having invented dynamite. But only a fiend in human form could have invented the Nobel prize."

The faith of the armourer — and the many international deals in which the rival European armourers participated — had curious results in the 1914 war. The weapons which were turned on the German, British and French armies had often been made by their fellow-countrymen. Krupp's guns were fired on the Germans by the Russians, British guns were fired by the Turks at the Dardanelles.

Nowadays arms trading is largely the province of governments. The Pentagon and the Kremlin are responsible for the lion's share. But Britain still sells upwards of £700 million worth a year in secrecy to mainly Middle Eastern governments. Anthony Sampson in The Arms Bazaar describes a visit to the permanent exhibition inside the Ministry of Defence of "British weapons for sale, displayed in a big central hall, the black heart of the ministry, where visiting potentates, generals and admirals are tempted with new instruments of warfare. 'This is what I call the naughty stuff,' said Sir Lester (Suffield), waving at one corner where mortars with maximum lethality were elegantly laid out on gravel like neo-realist sculpture."

Undershaft may owe something to Nobel or Krupp, the Prussian "Cannon King", whose paternalist welfare arrangements for his workers in Essen may have inspired Undershaft's model town. But Shaw believed Undershaft was one of his greatest creations of character. "The part of the millionaire cannon founder is becoming more and more formidable," he wrote, to the actor Louis Calvert, who was to play the part. "It will be TREMENDOUS, simply ... Undershaft is diabolically subtle, gentle, self-possessed, powerful, stupendous, as well as amusing and interesting. There are the makings of ten Hamlets and six Othellos in his mere leavings."

The Final Debate

The great debate in Act III between Undershaft and Cusins gave Shaw unwonted trouble, however. He scrapped and rewrote it because he did not want Undershaft to win too easily. Gilbert Murray offered suggestions which Shaw seems to have incorporated. "I want to get Cusins beyond the point of wanting power," Shaw wrote to him, "His choice lies not between going with Undershaft or not going with him, but between standing on the footplate at work, and merely sitting in a first-class carriage reading Ruskin and explaining what a low dog the driver is and how steam is ruining the country ... As to the triumph of Undershaft, that is inevitable because I am in the mind that Undershaft is in the right and that Barbara and Adolphus are very young, very romantic, very academic and very ignorant of the world. I think it would be unnatural if they were able to cope with him."

In the margin of a book about him, Shaw pencilled a summary which shows that there is more to Undershaft than an apology for capitalism: "Undershaft professes and shows himself a 'confirmed mystic', though he crushes Barbara by the contrast between the miserably charitable ration with which she bribes the poor to pretend that they are 'saved' and the high wages and organised welfare arrangements with which [anticipating Henry Ford, by the way] he saves them solidly from the degradation of poverty."

And indeed it is not a simple victory of argument, for it is Barbara, in the end, who goes "right up into the skies". Shaw had to admit "Even my cleverest friends confess that the last act beat them, that their brains simply gave way under it." It is possible that he was not as confident as he sounded in the victory of Undershaft's "hideous gospel", as Robert Blatchford called it in the Clarion. "The third act is so novel and revolutionary that it will never get across the footlights at one hearing," he wrote to William Archer afterwards, "You, wretched atheist that you are, must see it again tonight. It is a MAGNIFICENT play, a summit of dramatic literature." In that at least, he had well-deserved confidence.

George Bernard Shaw

| born in Dublin, 26 July 1856; | died at his home in Ayot St Lawrence, 2 November 1950 |

His plays (dates are of composition):

| Widowers' Houses (1885-92) | Pygmalion (1912-13) |

| The Philanderer (1893) | Great Catherine (1913) |

| Mrs Warren's Profession (1893-94) | The Music-Cure (1913) |

| Arms and the Man (1894) | O'Flaherty, VC (1915) |

| Candida (1894-95) | The Inca of Perusalem (1916) |

| Man of Destiny (1895) | Augustus Does His Bit (1916) |

| You Never Can Tell (1895-96) | Annajanska The Wild Grand Duchess (1917) |

| The Devil's Disciple (1896-97) | |

| Caesar and Cleopatra (1898) | Heartbreak House (1917) |

| Captain Brassbound's Conversion (1899) | Back to Methuselah (1918-20) |

| The Admirable Bashville (1901) | Jitta's Atonement (1922) |

| Man and Superman (1901-03) | St Joan (1923) |

| John Bull's Other Island (1904) | The Applecart (1929) |

| How He Lied to her Husband (1904) | Too True to be Good (1931) |

| Major Barbara (1905) | Village Wooing (1933) |

| Passion Poison and Petrifaction (1905) | On the Rocks (1933) |

| The Doctor's Dilemma (1906) | The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles (1934) |

| The Interlude at the Playhouse (1907) | |

| Getting Married (1908) | The Six of Calais (1934) |

| The Shewing Up of Blanco Posnet (1909) | The Millionairess (1935) |

| Press Cuttings (1909) | Cymbeline Refinished (1937) |

| The Fascinating Foundling (1909) | Geneva (1938) |

| A Glimpse of Reality (1909) | In Good King Charles's Golden Days (1939) |

| Misalliance (1909-10) | |

| The Dark Lady of the Sonnets (1910) | Buoyant Billions (1946-48) |

| Fanny's First Play (1911) | Shaks Versus Shav (puppet play, 1949) |

| Androcles and the Lion (1912) | Far Fetched Fables (1949-50) |

| Overruled (1912) | Why She Would Not (1950, unfinished) |