|

Loading

|

|

|

Directors as God

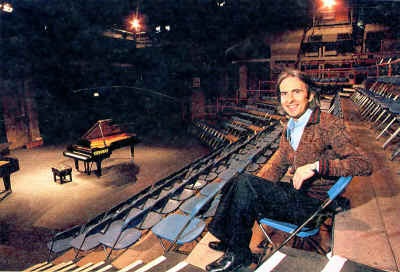

Directors have become the new stars of British theatre. Critics talk of Brook's Midsummer Night's Dream rather than Shakespeare's, Nunn's Macbeth rather than Ian McKellen's. Peter Lennon profiles Peter Gill, one of the directors most admired by critics and actors alike in The Sunday Times Magazine, November 26 1978.

If there is one predominant characteristic of the life of a theatre director - unlike an author or actor it must be that he is a figure of reproach.

If he takes liberties, even illuminating liberties, with a text he is upbraided for being insufferably arrogant; if he doesn't he is a dull technician. If he favours the classics he is said to be out of touch with the masses; if he puts on romps for the masses he is accused of being tediously trendy. And, unless he sticks to Shaftesbury Avenue, he is constantly being reproached for squandering the ratepayers'-taxpayers' money.

When Peter Gill agreed to become artistic director of Hammersmith's new arts centre the Riverside Studios last year he could not have known that he was about to step into a firing range on to which all anti-director missiles seem to converge. Including the new one Hammersmith social workers have bitterly let loose at him: "Perfectionist!"

The problem is that Hammersmith, a multi-racial borough of 170,000 souls with acute unemployment, is taking very uneasily and reluctantly to its new cultural cornucopia which has a £132,000 annual council subsidy.

Last January Riverside had a triumphant official opening with Gill's acclaimed production of The Cherry Orchard. Since then its two studios (formerly BBC television studios) and exhibition area have accommodated, among others, Mozart's Cosi Fan Tutte for two nights; The Tempest; The Changeling; The Ragged-Trousered Philantrophists; films for children, and late night movies for adults. There was a visit from a gratifyingly esoteric Japanese company, Tenjo Sajiki, and sell-out performances by Britain's first black dance company, Maas Movers.

At Riverside seats from 90p to £2.50 you can get everything from Monteverdi Madrigals to Arkansas's Fayetteville High School Choralettes.

Are the citizens of Hammersmith radiant with pride? No. Irate ratepayers and frustrated social workers regard Gill's Riverside Studios with some of the indignation that Christian lady vigilantes along the Mississippi reserved for the arrival of the gambling boat offering booze, broads and the pox. Social workers are sour about intellectual intoxication offered to a community in need of more curative draughts. Some ratepayers feel they are subsidising theatre for the exquisites of other, more elegant, boroughs.

Liberals hold the balance of power in Hammersmith and one of the two Liberal councillors, Simon Knott (a Riverside trustee) is highly exercised at the under-pricing of the seats, the occasional over-exposing of the actors (a visiting company showed their bottoms in The Tempest), and the lack of bingo facilities.

The target, Peter Gill, was born in Cardiff 38 years ago and educated in a Roman Catholic grammar school. Unlike the "Cambridge humanists" whom, he says, dominate much of the established theatre, he is not university and although admitting to a "posh" accent does not know exactly how he got it.

Gill is a slight figure, with some of that suggestion of chronic malnutrition which you often find in theatre people who have worked their way in from the provinces by way of fit-up companies. He has a way of tackling a point with passion and then, incompleted, trailing off into silence. Not, one gets the impression, because he has forgotten what to say so much as that he has plunged into a more interesting labyrinth of perplexing speculation which he finds too wearisome to dredge up verbally.

But there is nothing inconclusive about his stands on artistic matters, and none, once he has worried his way into the text, about how a production should be mounted.

Actors flock to him. People like Julie Covington and Eleanor Bron happily work for the £50 a week which is all Riverside can offer. (At the National an actor of average ability can get £120.)

The two sources of his love for the theatre could not be more popular. His father loved the music-hall and took him to all the great variety bills and lavish musical comedies at Cardiff's Empire and New Theatre. His mother was addicted to Saturday Night Theatre on the wireless, and he listened too.

His first encounter with the theatre was at school when a touring company put on Tartuffe and as one of the boys who helped to put out the chairs he was allowed in free. He was so fascinated by Moliere's description of a bourgeois hypocrite that he sat in on all the performances.

He went, briefly, to a local drama school and then took a job as assistant stage manager with an Arts Council touring company doing Look Back in Anger and She Stoops to Conquer. He went to London and began doing odd jobs at the Royal Court; and then directed D. H. Lawrence's A Collier's Friday Night in 1965. This was the first of a series of productions of Lawrence, Chekhov and Joe Orton which put him in a class with the Court's most original producers, William Gaskill, Anthony Page and Lindsay Anderson. In the Seventies he has also directed plays for the BBC and written three; at least one, Small Change (1976), has a high reputation.

Gill became involved in Riverside when Nick Raynsford, a former councillor concerned with leisure and recreation at Hammersmith, felt that after the closure of the old Lyric Theatre (1968) there was a need for a centre for the performing arts. Gill, a local resident, was asked to be artistic director.

Is he a director who finds in a few lines the key to a play? "No, I have no gift for extrapolating the whole meaning of a play from a few key phrases. That is very Royal Shakespeare. I do not have an `interpretative' approach. I get to know the play very well and then work with the actors and while I don't want to sound mystical, I don't really know how we arrive at the production we get.

"Initially we spend a lot of time working out a text on which we finally are all agreed. It is rare then that I am in direct conflict with an actor's interpretation. When I do it is appalling. I am not terribly manipulative. I can't spend days deviously trying to get someone to do something. When there is a clash it is unresolved.

"The first person I begin work with is the designer. The designer helps me learn about the play. It is better to start as soon as possible with the designer since your mind begins to become full of images which you should work on straight away. Ideally we should all start together. But the economics of British theatre, which does not allow anywhere as much rehearsal time as you get abroad, make it impossible for everyone to be in from the start.

"Authors like to come out of their study and be at rehearsals. But some have the problem that they cannot rewrite. Joe Orton was very good at rewriting. But I am riot in the business of restructuring plays. I am a writer myself and my sympathies are totally with the author. But in the end the play is the thing."

One of Gill's great preoccupations is with "trying to get the wax out of the audience's ears". Trying to get both the audience and young actors to appreciate verbal possibilities of a text, modern as well as Shakespearean. But he finds that audiences begin to fret when you "disturb their relationship to the expected kind of Shakespearean buzz".

One problem we have in Britain, Gill says, "is that we are used to getting our art too cheaply. Subsidy in countries like France is on an entirely different scale. Londoners don't realise how lucky they are. Actors tend to come to live here, which makes it possible for me to get them cheaply.

"The other problem is that this is a philistine culture. When we put on Chekhov the BBC went out into the streets and asked people did they know who Chekhov was. It's peculiarly BBC! Would they ask people who is Ian La Fresnais ? [Co-author of Porridge and The Likely Lads.]

"In this country the only real link between Buckingham Palace, Downing Street and the people is philistinism I'll get into trouble for that they tolerate artists, but only because of our tradition of tolerance, not because they appreciate artists."

Riverside is not as firmly anchored as it would like to be, despite its apparently huge grant from the council and a total of £40,000 annually from Arts Council sources. They still have to organise fundraising to meet costs. Theatres dependent on local government live in permanent insecurity: every new election, a hostile balance of power, could put them out of existence.

Gill's response to local pressure appears to oscillate between indiscreet exasperation and groaning resignation. "We do not have a mandate to be a community centre, and I don't believe you can start with bingo and lead people to avant garde. Nor is it our aim to put on amateur theatricals for the locals. We try to put on plays which people who like plays would really like to see. I put on The Cherry Orchard because it was a popular classic. We also have continual contact with the kids of the neighbourhood. We did some of the renovation work here with the aid of the Government's Job Creation scheme and a lot of the local kids worked here.

"I used to talk to them. `Shakespeare -wankers!' they would say. `Who told you that! You don't know for yourself' . . . I want to establish a creative core here. To have a workshop to keep in contact with those actors with whom I have worked creatively. What we have to do is preserve a creative atmosphere.

"The danger, if you are not careful, is that you end up doing what the politicians want, just to placate them. It is good, of course, not to be stuck in an ivory tower. To be working in such a close relationship to local politics is very, er, . . . educational."